ast Friday, August 22nd, marked a big anniversary for Project Lexa: five years to the day, we started development on the game. I know because August 22nd, 2020, was when I made the first git commit for the project:

Five years. Five years! That’s a long time to work on anything, especially a game project. Development timelines have always been a hot topic in indie game dev. Veteran indies tell you, understandably so, to always be cognizant of the total time you spend making a game: don’t overscope; don’t spin your wheels; kill ideas quickly if they’re not working and move on to the next thing. This is because the length of development time rarely correlates to financial or critical success. Some games take years to make and nobody plays them; others take less than twelve months to come together and are enjoyed by millions.

I say all this knowing I’ve gone against some of the sage advice from my indie colleagues. Project Lexa is a beefy game with a lot of big ideas that take a while to implement, but they’re also game ideas that I strongly believe in and get to work on with immensely talented collaborators. It’s also a game that, at present, we can only dedicate ourselves part-time to. All these circumstances and more lead to an extended development timeline, which, at times, can feel sluggish. But when I compare Lexa’s current state to where it was eighteen, twelve, or even six months ago, the progress has been immense.

So in celebration of our five year development anniversary as well as a reminder of how far we’ve come, I’ve written up a reflective dev blog on where we’ve been, where we’re at, and where we’re going.

Where We’ve Been

Before making that first commit, Nick and I talked over the course of many months about the possibility of collaborating on a game together. Once we decided we were going to give this collaboration a shot, we had to figure out what kind of game we’d be making. And if you haven’t realized from the setting of our game — or the work on Nick’s portfolio site or the merch on his shop Ultra Far Out — Nick loves sci-fi.

So it was no surprise that he suggested our game project should have a sci-fi setting, and I happily agreed! I was honestly more eager to work with someone talented like Nick than to try to force him into an idea I already had. And to be clear: I didn’t have any ideas for a game yet. I had just come off of a slate of different game prototypes that, for one reason or another, never came together. I was eager to start with a blank slate with few expectations and let an idea grow organically.

After exchanging some ideas back and forth, Nick offered up a pretty interesting concept: “what if it was about translating alien languages?”

I really took to that idea, thinking about what it would look like in practice. In the realm of puzzle games, I’m particularly drawn to ones that focus on lateral thinking — games like The Witness, Return of the Obra Dinn, or Outer Wilds — and thought that a puzzle game in that style focusing on conlangs would work really well. Of course, this isn’t an entirely new game concept; plenty of games have fictional language translation as either a core part of their gameplay — such as Heaven’s Vault or Chants of Sennaar (a game that happened to come out a few years into Lexa’s development, giving me a small heart attack for fear that our lunch had fully been eaten) — or as an optional deep dive for dedicated players — such as Tunic or Fez.

But there is still plenty of unexplored territory in this design space, so I immediately set to work on what our specific language design would look like.

Language Design: Our North Star

I’ve mentioned this before, but I’m always wary of saying too much about Project Lexa’s language for fear of giving the game away. However, since this is a reflective piece on our development so far — and the language is so core to the game’s design — I want to talk briefly about one linguistic concept that spurred a lot of the game’s early design work: morphemes.

Morphemes are basically the building blocks of written language — at least written English; I’ll admit I’m pretty ignorant of how this applies to other languages. There are several types of morphemes, but I’ll focus on just two: free and bound morphemes. Free morphemes are morphemes that possess full linguistic context by themselves. This applies to things like simple nouns, verbs, or adjectives — “cat,” “dog,” “walk,” run,” “happy,” “sad” — you get the idea. Bound morphemes are modifiers — specifically prefixes and suffixes — that attach to a free morpheme to change its meaning. So the bound morpheme “un-”, which is used to negate or invert the meaning of a word, can be attached to the free morpheme “fair” to turn it into “unfair.”

Project Lexa’s glyph language makes this linguistic concept its bedrock, but instead of having morphemes made up of groups of Latin characters (e.g. letters), all of our morphemes are represented by individual, pictographic glyphs. So “un-” and “fair” in our language would be two separate glyphs that need to be combined together to become “unfair.” How do you know which glyph is “un-” and which glyph is “fair”? Well, that’s the point of the game!

This was an early design discovery that made me super excited about the game. There was just so much possibility in mixing and matching glyphs to derive new meanings. With this idea firmly rooted, we had our next task ahead of us: turning this into an actual game.

Early Dev Days

While Project Lexa is, at its core, a puzzle game, I didn’t want to make it an abstract one, where all you’re doing is translating glyphs in a disembodied display with nothing else to ground it.

I love games with characters and story and worlds, and I wanted Lexa to have that. But I also knew that all of those aspects — character controllers and dialog systems and cutscene scripting and save systems and… — should come later. First, I had to solidify the glyph designs and translation mechanics.

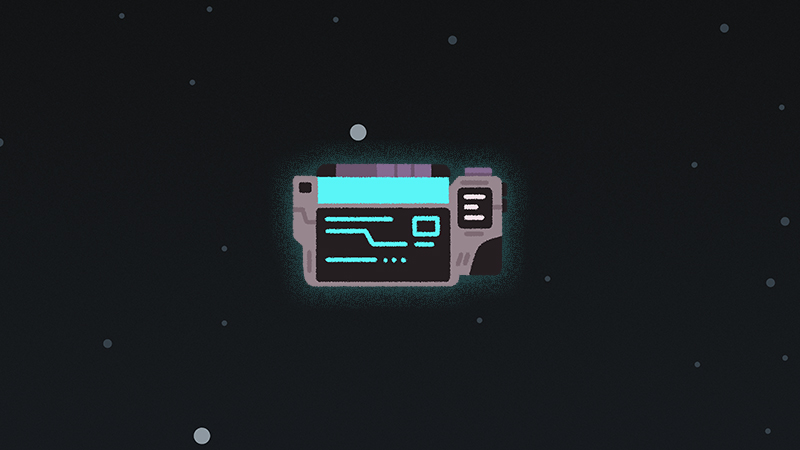

Here is a GIF of one of the first things I implemented:

This isn’t gameplay — though some folks thought it was when I first shared it on social media. It’s actually a development tool I built inside of Unity to design and save glyphs. Very early on I decided the glyphs should be confined to this 9-by-9 dot grid as both a visual motif and useful creative constraint, and I thought it might be easy to draw up the glyphs in-engine using line renderers and then export them, allowing for their convenient use elsewhere. And this tool was pretty robust: it allowed you to draw lines vertically, horizontally, and diagonally at 45 degree angles, snapping to any of the neighboring nodes; you could delete active lines by clicking on them; and you could export the entire glyph with a custom name that stored it in a dedicated directory.

Unfortunately, due to some complexity around loading Unity’s line renderers from memory, this did not make glyph management easier, so I soon abandoned the system in lieu of just importing glyphs from a sprite sheet, which was simpler and less error-prone. Sometimes, you build what you think is a cool tool only to realize it doesn’t save you any time, energy, or headache! Alas.

So instead, I just started drawing out a bunch of test glyphs in Illustrator, packaging them up into a sprite sheet using Photoshop, and importing them directly into Unity. The next step was to figure out how to interface with the glyphs to translate them. If you read my blog post on the iteration of Lexa’s translator, you’ve seen every major version of the translator, including the very first prototype:

This rough mock existed just to help lay the translator’s groundwork by answering questions like, “how do we target individual glyphs?” “How do we navigate a glyph screen?” “Where do we think important information on the translator will be located?”

I don’t think this version of the translator even had a keyboard — meaning I made a translator that couldn’t even translate. It just existed to get something on the screen to start thinking about interaction design. Slowly but surely, the translator evolved into what I’ve previously called Version 1, allowing for actual translation and more advanced interfacing with the glyph screens.

Version 1 of the translator in a Unity scene all by its lonesome circa late Fall 2020. This was the entirety of the game at this point in time.

And since a theme of this blog post is development time, I’ll mention that the time it took to go from the initial commit to Translator v1 was about three to five months of part-time development. All the while, Nick and I were frequently meeting to figure out the art direction of the game. By this point, we had agreed that the game outside of the translation mode was going to be a 2D, exploration platformer of some sort, which helped define some useful boundaries for the art style.

One of the first pieces of concept art he created is the header image for this post, where you can see a very early rendition of Lex in a room bathed in bright, highly-saturated colors. We eventually pulled back on some of the color choices, but Lex’s design was more iterative — plenty of the elements in this original depiction still exist now.

With Nick working on refining the art direction and me having the foundations of the translator system solidly in place, I set about building out the character and world systems with premade assets, with some horrendous programmer art later thrown in for good measure.

A very early prototype of Project Lexa’s overworld gameplay from February 2021, showing our placeholder character running between two spires. These spires were made to act like impromptu terminals, where interacting with one would allow you to open the translator.

The assets I originally used to build out the game was from a first-party Unity asset bundle called 2D Game Kit. 2D Game Kit has a lot of core features you’d want for building a standard 2D action platformer: a character controller for movement and combat, scripting and UI for dialog, camera logic, tile sets for platforms, pause screens, and so much more. It’s a great little bundle for just getting the core features of a 2D platformer up and running.

I mocked up a very basic test level with it, allowing me to have a character that I could move around and interact with nodes to contextually open up the translator. This came together around February 2021, about six months into the project. After half a year, I could finally visualize the two pillars of our game: the translation interface and the 2D world exploration.

Continuous Development

A screenshot of Project Lexa circa April 2023. Basically every part of the game at this point was still a work in progress: Lex was still a static sprite with no animations, much of the environment art was temporary, and the UI/UX for the interaction prompts was getting refined. The underlying movement code for Lex was actually just code from Unity’s 2D Game Kit at this point.

This started the continuous process of jumping between different aspects of the game and chipping away at them, little by little. Some weeks I’d focus on adding a new feature to the translator — maybe connecting it to a door so you could open it in the translator interface or adding some much-needed refinement to its suite of features — other weeks I’d focus on some aspect of the world or player logic — maybe Lex’s jump needed to be adjusted or it was finally time to add a missing feature to the dialog code.

Nick would also be continuously passing me new art assets, so I’d switch to implementing those whenever they came in so we could see how they looked in context. And as we added other awesome members to the project, I would jump around implementing their contributions as well: puzzle designs, dialog writing, music and sound effects, and so much more — a symphony of different disciplines harmonizing.

You do that for long enough, and eventually, you have a video game.

Where We’re At

So that has been the arc of the project so far: the initial ideation phase with Nick, then a prototyping phase with programmer art and Unity’s 2D Game Kit, and now a continuous, iterative production phase.

Recently, I found an awesome web-based tool for extracting still frames from video files, and I found it really useful to grab nice screenshots from Lexa footage. Here’s one of the screenshots I snagged:

A screenshot of Project Lexa from June 2025.

The more I look at this, the more I’m impressed with how far we’ve come — we have character animations, full backgrounds and tilesets, and more. Compare this to the 2023 screenshot, and the difference is quite stark. Heck, half of what’s in the game now wasn’t even there in 2024. I can’t wait to compare this screenshot to how the game looks in 2026.

Where We’re Going

So what does the path ahead look like?

I’ll answer that question with an evergreen tweet from Ben Esposito, developer on Donut County and Neon White, one I’m sure many of you are familiar with:

Even if you understand how complex even the smallest game can be, it can still leave you unprepared for how much work it entails to bring it from concept to a final, polished product. Every aspect — from the character controller to the user interface to the save system and more — all have to be designed, engineered, and tested, mostly from scratch. Plenty of add-ons, assets, and engines help with this process, but you usually have to add a healthy amount of additional work to make it your own (I’m currently cooking up another dev blog about how we are utilizing and extending Yarn Spinner for our dialog system).

And don’t be mistaken: Project Lexa is not a small game. But with more and more of the game’s core systems becoming feature complete, the workload continues to get easier and easier. Once these systems are fully featured, the main hurdle for the game will simply be content generation and polish, and at that point, the pace of development will feel exponential.

All of that will come in time. For now, I wanted to reflect on how far we’ve come, how excited I am for what the future entails, and to thank folks for following us on this journey as we continue to make Project Lexa the best it can possibly be.

Until next time!